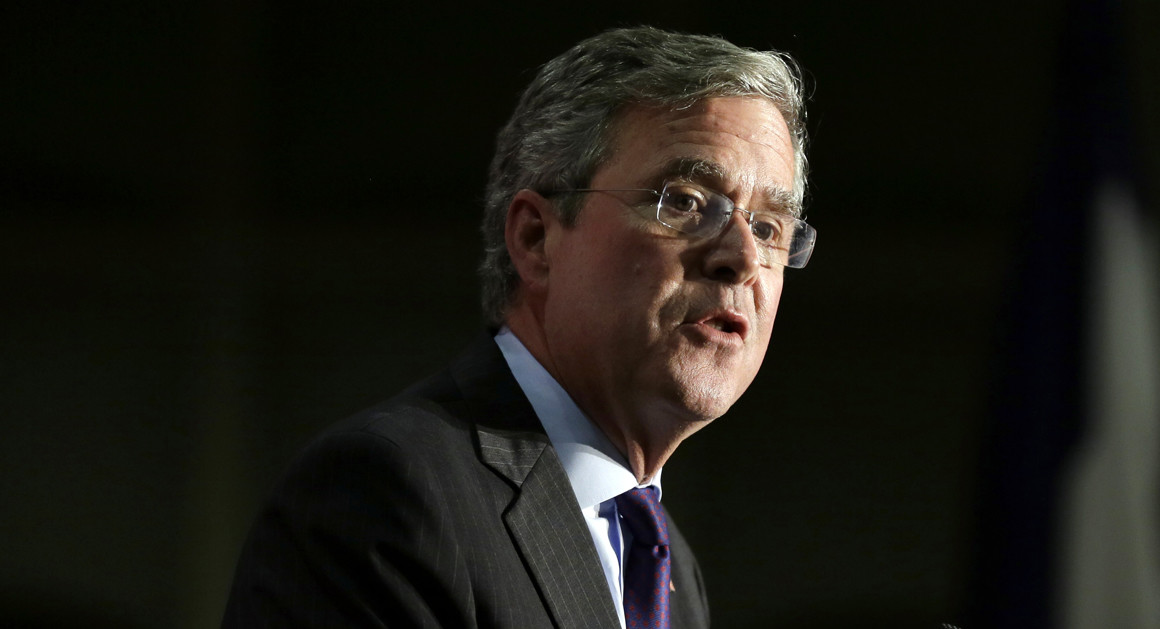

Jeb Bush will reach back to his own legacy as Florida governor on Tuesday to unveil his vision for replacing Obamacare, showcasing what he calls state-tested ideas for bringing down health care costs and revamping health coverage for the poor.

But Democrats are ready to make the case that his record in Florida is nothing to emulate — that in particular, his changes to Medicaid harmed Florida’s poorer residents, something that could make him vulnerable in the general election if he becomes the GOP presidential nominee.

Without a doubt, Bush became a darling among conservatives by privatizing parts of the state’s health care program for the poor — placing him among the first governors to move in a direction now considered commonplace and earning him The Weekly Standard’s “best governor in America” title in 2006.

“What he proposed didn’t work,” says Florida Democratic state Sen. Eleanor Sobel, vice chair of the Senate’s Health Policy Committee. “There was no punishment for not giving people services.”

And the state’s uninsured rate climbed under his tenure, becoming one of the highest in the nation. Were Obamacare to be repealed, more than a million Floridians would lose health care coverage.

Still, in his speech Tuesday at St. Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire, Bush is expected to offer many of the ideas that animated him as governor, along with others long championed by national Republicans. He wants to spur private-sector innovation by rolling back federal government dictates, as he once sought to do by privatizing Medicaid. He would change federal tax law by capping the tax break from employer-sponsored insurance in a bid to lower insurance premiums and provide federal tax credits to help people buy insurance that would protect them against “high cost medical events.”

He would return much of health care control to the states — along with capped federal funding, although he does not explain how that amount would be set.

And he would provide a transition “for the 17 million individuals entangled in Obamacare,” although he does not elaborate what that would be.

Bush’s health care speech comes at a time when the candidate once cloaked in a mantle of inevitability must distinguish himself among a crowded Republican field. The Republican base is clamoring for non-establishment outsiders like Donald Trump, Ben Carson and Carly Fiorina.

In the speech, Bush will make the case that he’s the GOP presidential candidate who has the experience not only to repeal Obamacare — as all of his rivals vow — but also to replace it with something smarter and better.

He is expected to mention how in 2006, his administration launched a pilot program to transform Medicaid coverage and tackle its rising costs in two counties. In a sweeping application to the federal government, his administration promised nothing short of a revolution. “Change cannot be timid or tentative,” it promised in August 2005. “It must fundamentally transform relationships, responsibilities and economic incentives.”

Bush’s goal was to tame the costs by handing more control over to private insurance companies. The plans would decide, with less government intervention, the types of benefits they would offer and, in turn, would assume the risks of any rising costs. The idea was to allow Medicaid beneficiaries — like those covered by private insurance — to pick their choice of plans with the hope that market forces would make care better as well as more affordable.

But rather than allowing more choice to improve upon traditional Medicaid, Bush’s liberal critics say he gave private managed-care plans too much leeway to design the benefits, which allowed them to “cherry-pick” the healthiest, lowest-cost beneficiaries. Networks of hospitals and doctors were limited. And consumers found the lack of standard benefits confusing; some ended up with inadequate coverage that didn’t give them the health care they needed.

If anything, the Bush Medicaid pilot program is less revolutionary now than it seemed back in 2005, says Diane Rowland, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Many states are now moving toward managed-care plans that pay insurance companies per patient and then give them more flexibility in the types of benefits they offer.

“It’s hard to think of him as someone who turned the health care system upside down,” Rowland says. “He was doing what many other governors continue to do, which is figuring out how to link Medicaid payments to make the budgets more predictable.”

A 2008 Kaiser Family Foundation analysis shows there was great, initial confusion among the disabled and poor people who received Medicaid services. Much like the chaos surrounding the rollout of the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid recipients were confused by the new plans and the doctors to whom they had access under them. Fifty-one percent of doctors surveyed by the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute said it was harder to provide medically necessary services to children on Medicaid because of its restrictions.

Overall, Bush’s pilot program did lower costs. The Medicaid costs for pregnant women and children in the pilot, for instance, decreased by $1 per month for HMO enrollees, according to an analysis done by Health Services Research and funded by the Florida government.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of residents lost private health coverage as a result of the weakening Florida economy — the rate increased from 17.4 percent when Bush took office in 1999 to 19.8 percent when he left in 2007, according to U.S. Census data.

“The rhetoric and the reality were two different things,” says Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown Center for Children and Families. “When the concept was rolled out, it was very much about injecting these market-based principles into the state in a radical way. That is not really what happened at the end of the day.”

Alker also warns about what would happen if Bush tried to roll back requirements on the benefits insurance companies should cover on the federal level, as he did on the state level. “The federal protections are very important to protect beneficiaries, many of whom are very vulnerable,” she says. “Medicaid is an important program for people with disabilities, the poor and seniors. It’s risky to go down the path that I believe he would want to go down."

Bush’s Florida experiment and the control that it gave to the state will inform much of his health care speech. “You’ve got a guy who has a strong conservative track record of empowering consumers and providing information and using technology. His track record speaks for itself,” says Alan Levine, Bush’s former health care secretary in Florida.

Aiding Bush is his health care policy adviser, Stephanie Carlton, a former McKinsey health consultant, nurse and long-time Hill staffer who worked under Sens. Tom Coburn, John Cornyn and Orrin Hatch. She’s well-liked among conservative establishment wonks and by Hill staffers, some of whom now populate D.C. lobbying shops.

And she’s helping Bush by drawing upon her contacts from the federal government and the private sector to help the campaign think through its health care ideas over roundtable discussions, phone calls and one-on-one lunches with informal advisers.

But even with Bush’s Medicaid record in Florida, voters should expect scant specificity. It never behooves candidates of either party to unveil reams of policy details a full year ahead of the election and in full view of opposition researchers. The Republican base’s primary concern is killing off Obamacare as quickly as possible, and the details come second to that.

- Publish my comments...

- 0 Comments